inside/outside … sort of

april 24, 2011 § Legg igjen en kommentar

the not knowing

april 15, 2011 § Legg igjen en kommentar

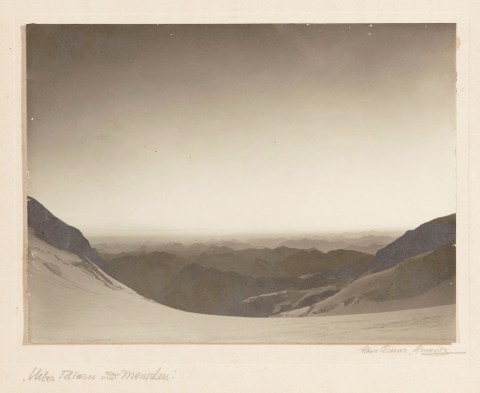

Albert Steiner, Über Tälern und Menschen

… hvis en slik, på en samme, stille, skjønne, melankolsk måte kunne få vasket huset sitt og fått orden på kontoret, system i alle papirene som flyter sammen med alle ordene langt inne og forsvunnet i datamaskinen, denne herskerinne, denne noen ganger onde herskerinne som tar ut biter slik at det som før hang sammen er blitt til gåter uten svar og svar uten gåter, løse ender, forbindelsene ikke til å finne, ubegripelige, matte minner som aldri igjen kan bli fine strømmer som lyser overhodet/ over hodet … en får nynne. Melankolske melodier.

inside/outside

april 12, 2011 § Legg igjen en kommentar

inside/outside/igjen

april 11, 2011 § 1 kommentar

Untitled Facade by Jim Kazanjian, og jeg vet ikke hva det er, men overgangen mellom inne og ute slutter ikke å fascinere. Denne forviklingen som alltid er i oppløsning. Et ingensteds. Et mellomrom. En glipe, som om det var mulig å, om ikke se eller høre noe gjennom den, så ane, – og kanskje skrive det.

Untitled Facade by Jim Kazanjian, og jeg vet ikke hva det er, men overgangen mellom inne og ute slutter ikke å fascinere. Denne forviklingen som alltid er i oppløsning. Et ingensteds. Et mellomrom. En glipe, som om det var mulig å, om ikke se eller høre noe gjennom den, så ane, – og kanskje skrive det.

artemis dreaming

april 4, 2011 § 4 kommentarer

nødvendig å kommer seg forbi gårsdagens innlegg med et som står i sterk kontrast. her finnes ingen irritasjon forkledd som ironi. her er lys og skygge, harmoni og ingen mennesker i naturen bortsett fra Edward Steichen som fotograferer og kaller det Artemis Dreaming. og så kan jeg begynne dagen. skrive kanskje 1000 ord. til distant musikk av This Mortal Coil, Song to the Siren.

World Watcher

mars 23, 2011 § 3 kommentarer

Tenk om det sitter en stor, stille, rolig én og ser ut over menneskeheten og labyrintene der vi myldrer og aldri, aldri får lyst opp i krokene. Tenk om det sitter én og har overblikket over de talløse aspektene ved alle hendelsene og alle tingene. Tenk om det sitter én og kan se at en ulykke et sted, en storm, et skred, en forelskelse er en nødvendighet og til velsignelse, eller i hvert fall en nokså nyttig del av balansestykket som gjør at vår verden ikke faller sammen og ned. Og knuser. Mot bunnen av universet. Tenk om det sitter én og lytter og hører ropene fra de sårede, bønnene fra de savnede, sukkene fra de knekkede og vet at de bærer, de bærer med vinder og understrømmer. Og annet sted, kanskje til og med i en annen tid, veksles de, ofte sent, men aldri for tidlig, inn i barmhjertighet. Tenk om det sitter én og nikker med hittil ukjent tyngde og vekt og kan bekrefte det.

Tenk om det ikke finnes nåde i all evighet.

World Watcher by Jack Spencer

terence davies/of time and the city: A love song and a eulogy

mars 21, 2011 § 1 kommentar

Og jeg kan aldri glemme en scene fra Distant Voices, Still Lives, Terence Davies film om sin egen familie på 40 og 50 tallet i Liverpool: En ung kvinne står i en døråpning og ser inn i et trapperom, venter, så synger hun, går rundt seg selv noen ganger mens hun synger en sang. Det finnes noe filmscener og de er ikke dramatiske en gang. De er ofte så stille.

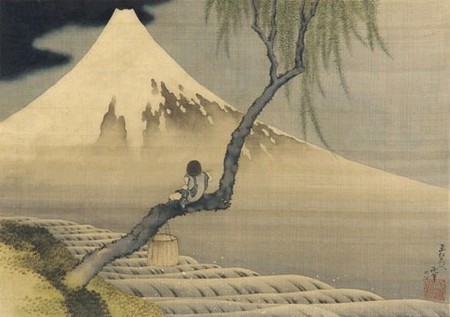

36 Viuws of Mount Fuji for Japan

mars 17, 2011 § Legg igjen en kommentar

Katsushika Hokusai laget en serie på 36 med Views of Mount Fuji. Han produserte under 30 forskjellige navn i løpet av livet. Mot slutten som «Gakyo Rojin Manji» (The Old Man Mad about art). «The Great Wave of Kanagawa» er også et av verkene fra 36 Views of Mount Fuji.

“ From around the age of six, I had the habit of sketching from life. I became an artist, and from fifty on began producing works that won some reputation, but nothing I did before the age of seventy was worthy of attention. At seventy-three, I began to grasp the structures of birds and beasts, insects and fish, and of the way plants grow. If I go on trying, I will surely understand them still better by the time I am eighty-six, so that by ninety I will have penetrated to their essential nature. At one hundred, I may well have a positively divine understanding of them, while at one hundred and thirty, forty, or more I will have reached the stage where every dot and every stroke I paint will be alive. May Heaven, that grants long life, give me the chance to prove that this is no lie. ”

Hokusai

The Prinzhorn Collection

mars 16, 2011 § 3 kommentarer

The Prinzhorn Collection er en samling arbeider psykiater og historiker Hans Prinzhorn samlet gjennom sitt arbeid med med psykisk syke ved Univeristetssykehuset i Heidelberg i Tyskland i 1920-årene. Samlingen som finnes Universitetet i Heidelberg består av rundt 5000 arbeider laget av 450 pasienter.

» [… ] Josef Forster (born in 1878) has only one untitled work, created after 1916. This became an emblem of the Prinzhorn collection, as it is an utterly Modernist piece in the Expressionist style. In this rough painting, a boy in a black suit with a blue scarf over his face is barely standing on stilts. The white sky above him could be a blizzard; the grass is a coarse green, peppered with black. In the upper right-hand corner of the painting, Forster explains his image: «This is to show that when somebody’s body does not weigh anything anymore, they no longer need to complain about their weight and are able to glide very quickly in the air.»

Wunder Hirthe by August Natterer. «Natterer was an electro-technician and unsuccessful scientist who went bankrupt. He was haunted by hallucinations after his business failure, and began to believe that he was a messenger of God. Later in life, he thought he was Napoleon IV. These imaginary lives supply the visions for his works, which, not surprisingly, made Neter a hero of the Surrealists.»

«Else Blankenhorn grew up in a bourgeois family, and was active culturally and socially. She played the piano and sang until she lost her voice at the age of 26, the result of neurasthenia. Later, she suffered from hypochondria, then nightmares. Her gouache works are scenes from her imaginary life, in which her alter ego lived with Emperor Wilhelm II. As his spiritual wife, «Else von Hohenzollern,» she produced banknotes featuring flowers and her angelic image in multiples, for the purpose of helping not the living, but dead lovers in need of redemption.»

» Oskar Herzberg, with no record of his birth or death, was hospitalized in Vienna from 1912 to 1914. He claimed to be a composer and a news vendor, but, in reality, his profession was servant. His works dominate a room and include pencil drawings (on ruled paper) and colorful works of gouache over pencil drawings depicting vivid and mainly happy scenes of life, like an afternoon on the ski slopes or a cheerful row of more than three dozen singing boys, titled Castrati.»

Letter written to her husband by Emma Hauck.

Letter written to her husband by Emma Hauck.

De engelske tekstene over er hentet fra artikkelen Messages from the margins skrevet av Tony Ozuna i Praguer Post.

The Prinzhorn Collection

Psychiatric University Hospital in Heidelberg

Hans Prinzhorn, Artistry of the mentally ill 저자

In his book, Prinzhorn first develops a theory of personal expression for creative production. He enlists a complex model involving various partial drives in an attempt to explain the phenomenon of Bildnerei (roughly “artistry” in English – he deliberately avoided the word for art, Kunst, for he considered it too loaded) in terms of the psychology of the creative urge. The second part of the book then examines the representations of schizophrenic patients, and dedicates a section each to ten such artistically active patients. Although he also affords the reader a glimpse into the ten people’s life histories and personalities, Prinzhorn’s interest here is directed more to analysing the works by empathic means (Prinzhorn also talks of “Wesensschau”, or primal insight). The third part deals with diagnostic questions and parallels to other forms of creative expression. Here Prinzhorn not only draws comparisons to thehttp://smileb.tistory.com/plugin/CallBack_bootstrapperSrc?nil_profile=tistory&nil_type=copied_post art of children and so-called “primitives”, but also to contemporary art. He explains the similarities in the latter to the patients’ works as being due to a “schizophrenic feeling of existence” that could be witnessed among his contemporaries. In his view, this reflects essentially an “ambivalent dwelling on the state of tension prior to making decisions”, which had also been determined among the mentally ill. Comparable efforts made in the artistic realm do not, however, result in the same success, because “healthy” individuals largely lack the ability to tap the unconscious during spontaneous creativity. Prinzhorn compared the “genuine” works of the schizophrenics with the “rational substitute constructions” of the leading artists of his day, and came up with an unconventional and radical critique of civilisation one that appears to have been the actual impetus for his book. His own position can already be compared with that of Jean Dubuffet, who was later to refer to himself as a “discoverer of discoverers”.